Jacqueline Stojanović on Colour Ways and Weaving as a Vessel for Preserving Cultural Heritage

When looking at paintings, Jacqueline Stojanović is more interested in how the canvas was first constructed rather than the painting itself. Her curiosity with preliminary and foundational tools for construction extends through her artistic practice of weaving, and combining unlikely materials such as steel frames with wool, and coloured pencil on wooden blocks.

Jacqueline’s solo exhibition Colour Ways is currently on view at Haydens (Naarm/Melbourne), initially as part of Melbourne Design Week, and open for an extended period until 22 June. Melbourne Art Fair speaks with Jacqueline about the challenges of continuing traditional weaving practices in a contemporary Australian context, her interest in the foundational construction of things, and the meeting of three bodies of work for Colour Ways.

Are you able to expand on the conviction, firmly present in your practice, of weaving as an ancient carrier of culture?

Weaving was one of our primary technologies as humans. It’s a practice that we all share a history with, and for some the history is more distant than for others. In my own case, the traditions continue in my familial context, and I reflect on the weaving practices of my parent’s homelands in former-Yugoslavia and Vietnam. In particular, the Pirot carpets of Serbia, which have acted as talismans in my home in Melbourne. These handmade textiles are portable fragments of our biographical home on the other side of the world. When borders dissolve and people migrate, these woven folk objects such as carpets, bags, clothing, and shoes allow us to carry culture with us in a visible way. They become physical representations of a broader landscape usually accessed through memory alone. Culture is formed through daily practices, and while hand weaving is no longer widely practiced, these objects of the past can carry with them the stories, landscapes, economies, architecture, ecology, as well as shifts in social, geographical and political movements of the hands that wove them. In this sense I view them as vessels of cultural heritage and pathways to lost knowledge.

Jacqueline Stojanović, Adria (installation view), 2024, wool, cotton, satin on steel mesh, 180 x 540cm. Courtesy the artist and Haydens.

Jacqueline Stojanović, Adria (installation view), 2024, wool, cotton, satin on steel mesh, 180 x 540cm. Courtesy the artist and Haydens.

How does your exploration and appreciation of weaving practices from diverse cultures – including former-Yugoslavia and Vietnam – inform your contemporary practice?

I began to consider weaving within my contemporary practice after spending time with the women weavers at Damsko Srce in Pirot, Serbia. This town is famed for producing handmade Pirot carpets, but upon my visit I understood that this practice was dying before my eyes. Currently there are only six women who continue to weave there, a significant decline from the nearly 2,000 who lived and worked in Pirot four decades ago. I felt a sense of urgency in continuing the practice in this instance. The carpets are protected as UNESCO world heritage artifacts and can only be considered Pirot carpets if they are made in the town of Pirot with the wool of the pramenka sheep which grazes on the nearby mountains – also an endangered species. Aside from the geographical limitations, very few people these days understand the meaning of the motifs depicted on the carpets, and without their meanings they become abstract to the viewers. This is a specific example, but not an uncommon situation within the wider practice of traditional arts. I was really fascinated by this, and moreover I continue to feel perplexed, that while I’m Serbian and can weave on a Pirot style loom with traditional motifs, any carpet I make would never be considered a Pirot carpet because of this geographical certification – a clear roadblock in continuing cultural practice for nations with far reaching diaspora. So, while I cannot make the carpets themselves, I continue to explore the themes embedded in the carpets, such as abstraction and mnemonic landscapes, as well as their formal attributes of the foundational gridded structures of weaving and Byzantine perspective. On the other end of the spectrum, I’ve been just as perplexed to see the situation with the textile industry in Vietnam, which grows rapidly with the global demand for skilled labour and competitive production costs. A situation that spurs on the consumption of fast fashion. It’s a kind of double-edged sword for the local economy and I’m beginning to consider these themes around shifts in social and material values through my contemporary practice as well.

What drew you to weaving, both by hand and through the loom, as a channel for artistic expression?

Very simply some things feel more natural than others, and for me this was weaving. But more broadly, I am curious about the foundational construction of things. When looking at paintings I’m more fascinated with how the canvas is made than covering it up with oil and pigment, as well as works on paper. I’m curious about the paper itself, which historically has been made with waste fabrics. My first loom was gifted to me by my mentor John Nixon, who encouraged my sensibility towards weaving. Through his mentorship I came to learn about the histories of weaving practices at the Bauhaus, within Modernism and in architecture. These histories also felt foundational to me and helped in paving a clear path for me to pursue weaving as a medium for artistic expression.

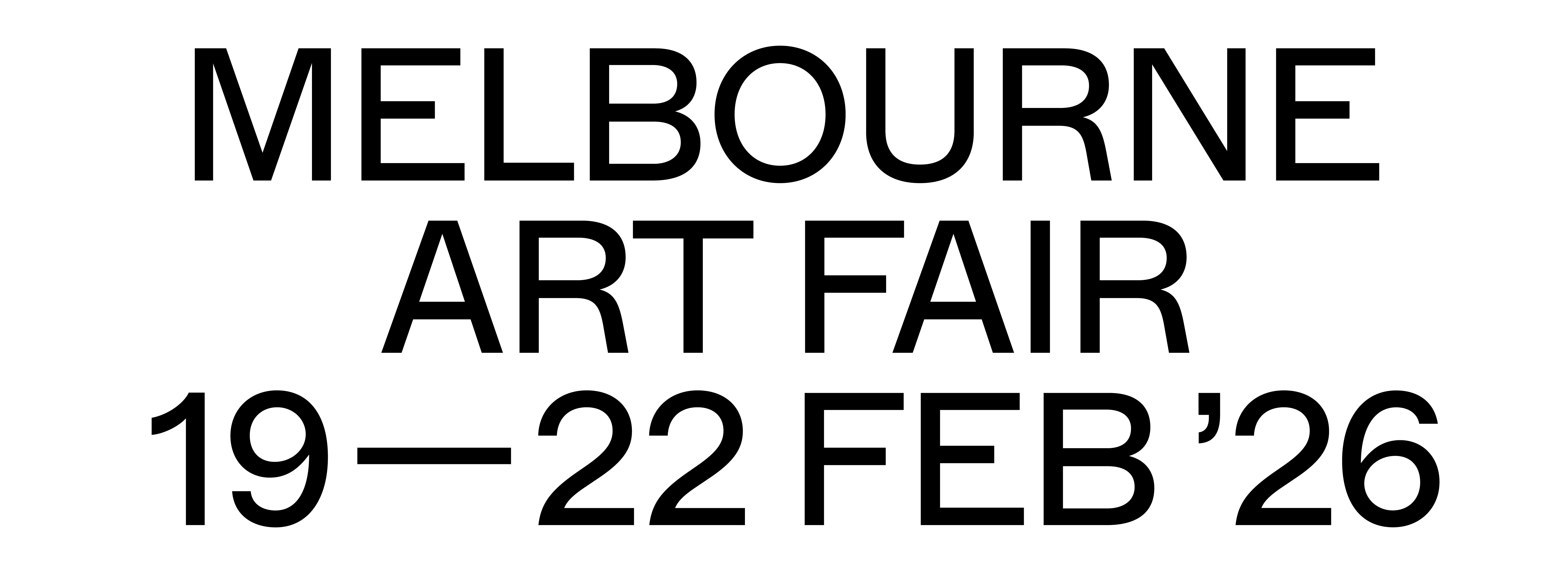

(Left) Jacqueline Stojanović, Pistil II, 2024, lacquer on wood, 17.5 x 17.5 x 2.5cm. (Middle) Jacqueline Stojanović, Column II, 2024, coloured pencil on wood, 20 x 5 x 2.5cm. (Right) Jacqueline Stojanović, Rampart II, 2024, coloured pencil on wood, 17.5 17.5 x 2.5cm.

(Left) Jacqueline Stojanović, Pistil II, 2024, lacquer on wood, 17.5 x 17.5 x 2.5cm. (Middle) Jacqueline Stojanović, Column II, 2024, coloured pencil on wood, 20 x 5 x 2.5cm. (Right) Jacqueline Stojanović, Rampart II, 2024, coloured pencil on wood, 17.5 17.5 x 2.5cm.

In addition to weaving, your multi-disciplinary practice draws from abstraction to create carefully assembled compositions using a variety of materials. Can you speak to the kinds of materials you use and the significance of incorporating these in your works?

The materials I select to work with share a thread in their common usage as preliminary or foundational tools. In Colour Ways these materials include steel mesh, which is commonly used for reinforcing concrete in the context of construction; wooden blocks, which are associated with early development, building, and play; and graph paper, which is used in planning woven textile designs. Each of these materials foreground gridded structures, which become natural compositions for me to assemble my ideas around. The grid is at the core of woven textile design and through practicing weaving it has become a device second nature to me for inscribing visual language. There is an honest element of exposure through using these materials as well, their rudimentary nature leaves no questioning in their making. They simply are, and there is something very satisfying and curious to me in merging materials that are unlikely to be coupled together, like wool and steel, or coloured pencil and pine. This material language draws on memories, motifs, folk traditions, and landscapes, funnelling them into my own interpretations through physical processes.

Can you describe the significance of ‘arrangement’ in Colour Ways, how does the colourway term reflect within the exhibition?

A colourway is a term ordinarily used within a design context to refer to the available arrangements of colour for a particular design. It’s my view that each person has their own colourways, and perhaps this can change over time, but what interests me is why we’re drawn to some colours over others. Where do our associations of preference stem from? In my practice I find colour to be an intuitive exploration, often evoking memories of experience and place or sounds. But the exhibition title takes a second meaning as well, referring to my process of making, whereby one colour leads to the next, and to the next, and so on, leaving even me surprised when finished and viewing the colourway as a whole. This process in part removes the element of design from the term, exploring the relationship between colours themselves, and providing the work with its own pathway to completion – a way through colour.

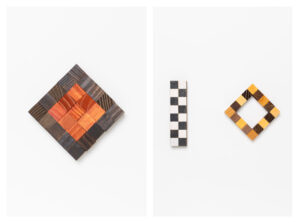

(Left) Jacqueline Stojanović, Untitled (1mm squares), 2024, coloured pencil on graph paper, 29 x 20cm. (Right) Jacqueline Stojanović, Untitled (1mm squares), 2024, coloured pencil on graph paper, 29 x 20cm. Courtesy the artist and Haydens.

(Left) Jacqueline Stojanović, Untitled (1mm squares), 2024, coloured pencil on graph paper, 29 x 20cm. (Right) Jacqueline Stojanović, Untitled (1mm squares), 2024, coloured pencil on graph paper, 29 x 20cm. Courtesy the artist and Haydens.

To enquire about Jacqueline’s works, click here to contact Haydens.

Subscribe to the Melbourne Art Fair newsletter to receive monthly updates on leading Australasian gallery exhibitions, artist interviews, insights and more throughout the year.

Melbourne Art Fair returns in the Victorian summer, 20 – 23 February 2025, at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre.. Participating galleries and artists announced in October 2024.