READ | Emma Buswell on Market Scares, embracing slowness, and her new tapestry for MAF

Emma Buswell knows her way around a knitting machine, a pair of knitting needles, and just about every textile-based art format in between. From formative years spent hand-knitting to later adopting a second-hand knitting machine, her practice is defined by a commitment to slowness (perhaps masochistically so), maintaining sustained attention on her tapestries long after the process stops being enjoyable and becomes physically taxing.

Often beginning as jokes or moments of frustration, the ideas behind Buswell’s work are painstakingly researched and stitched with layers of meaning, moving between grand mythological narratives and, more recently, reflections on what it means to live a good life within the constraints of late-stage capitalism.

Read on as Buswell reflects on her path into textile practice, her recent exhibition with Sydenham International, and the work she will present at AVA’s booth at Melbourne Art Fair 2026.

How did you first find your way into textile art? What drew you to the medium?

I’ve always been interested in making things. As a kid I used to sew small bears and characters out of scraps of felt and spent lots of time knitting very ugly scarves; later it became making clothes, drawing, painting. Like a lot of people, I drifted away from those impulses when I went to university and became heavily interested in theory, history and the sociology of art.

A few years after graduating, I worked on a project that involved a lot of rushed hand knitting and realised there had to be a faster way to produce knitted fabric. That led me to finding out about knitting machines. I bought my first one from an eBay listing in the US and it arrived several weeks later, rusty, caked in old plastic, and mostly incomprehensible. I tried it once, hated it, and put it away for six months. I’ve spent the last five years slowly teaching myself how to use it properly.

That slow, stubborn process ended up being really formative, and alongside my arts working practice made me reconsider my relationship to time, labour, value, and care.

Chook bag, Coles bag, money bags. These elements of everyday capitalism inject a sense of humour in your work while simultaneously subverting capitalism through their making. Can you expand on how capital essentially becomes a character in your work, especially in your recent exhibition with Sydenham International?

Funny story, the first idea for the work from the Sydney show came about from some experiences I had visiting an art fair for the first time in Taiwan at the beginning of last year. I saw someone walking around with a customised Christian Dior tapestry tote bag that they’d had designed to say Grocery Bag on the side. It was one of the most hilarious and simultaneously grotesque demonstrations of casual wealth I’d ever seen. Later that week, I bought some stuffed toys for my niece as a souvenir. One of them was a Shawn the Sheep toy and as it peered up at me from the dark void of the otherwise empty shopping bag, I got this idea for a series of soft sculptures that could behave as some kind of Muppet come nightmare fuel, come warning sign.

Thinking about capital as this kind of animated character, became a useful device for me. Capital dominates our lives in very intimate and irritating ways. I think about money not as an abstraction, but in practical units, how many weeks of rent something might cover, how much time a task consumes relative to its supposed value. For instance, the money bag which is called Bump in the Night in the Sydenham Show took over four months to create, and is entirely encrusted in small glass beads which have been hand embroidered onto the surface. Of all the works in the exhibition that one took the longest to produce.

Collectively, the works in that exhibition are all part of a series called Market Scares, which continued a fascination with the various powers and systems that dominate our lives, from the menial to the existential. What does it mean to live or attempt to live a good life within the constrains of late-stage capitalism? Using familiar forms like shopping bags or money bags lets me borrow the visual language of everyday commerce, but remake it through slow, labour-intensive techniques that are completely at odds with what those objects usually represent.

Emma Buswell, Market Scare, installation view, Sydenham International, 2025.

Emma Buswell, Market Scare, installation view, Sydenham International, 2025.

How does the physical process of making inform the conceptual side of your practice? With your larger tapestries especially, the time required for planning and weaving feels deliberately counter to capitalist rhythms.

I was talking to a friend about this recently actually. We both initially make work from big gestural vague kind of lines, and then over subsequent weeks and sometimes months meticulously refine those initial marks into this other kind of thing. The making and the thinking are inseparable for me. It all comes back to labour and time, the physical limits of the machine, the repetition, the errors; all of that feeds back into the ideas. Large tapestries require an enormous amount of planning and an even larger amount of time to execute, and that slowness isn’t accidental.

I will generally spend a lot of time thinking about a topic or idea and then lots of visual research takes place, going back through archives, phone notes, scrap bits of text I’ve recorded and then produce a digital image, or a cartoon that forms the basis for the work. That image is then charted into a graph, sometimes 10000 stitches by 1000 rows of work and divided up into lengths that are knitted on the machine. Everything is knitted in reverse as you’re always working from the back of a piece and then finally all the individual threads are woven in, the panels are stitched together, and the piece is wet blocked. I kind of enjoy the joke in spending months of time meticulously translating the immediacy of a rough digital sketch into something that resembles tapestry. Often the first time I will see how a work has turned out is the same moment the audience will as they are too big to stretch or show upright in my own studio. So it’s pretty nervy, and I can get quite anxious about how they will turn out.

Sometimes these pieces will take months to work on, depending on the complexity of the image, and I work long hours when I can into the rhythm of it. It’s quite meditative but also physically taxing. Often, I’ll find myself not noticing that six hours have past, and I might have knitted 50 rows of one panel that requires 800 rows haha. Working at that pace forces a kind of sustained attention that’s increasingly rare in other parts of my life. In that sense, the process for me has become a quiet refusal of capitalist rhythms, not in a particularly grand or heroic way, but through accumulation, patience, and staying with something long after it stops being enjoyable.

Emma Buswell, Laertes and Lethargy, 2023, courtesy of the artist and AVA.

When creating a new body of work, where do you usually start? With a concept, a moment in history, or something else?

It can be different every time, but usually works develop out of frustration. They kind of become an exorcism of sorts; of the things which haunt me, be that financial, political or everyday annoyances. Half the time they start off as jokes. I’ll write down initial ideas and then do research into the circumstances that may have came about to cause that issue. The notes section on my phone is diabolical, and sometimes I’ll only revisit a thought months later. Generally what results is a kind of big soup that meanders around an idea or a sensibility.

Over the last few years, I’ve become increasingly interested in storytelling, and in mythology both ancient and contemporary, in how grand narratives might show up in mundane forms. Starting from the everyday allows me to move between humour and critique without becoming overly didactic, but at the same time it also provides a kind of springboard for sharing ideas, a kind of grounding. Found images and references get collaged, overlaid with text, and then reinterpreted through stitch, letting the material do some of the thinking and work for me.

Your works often come off the wall, whether it’s a sprawling tapestry across the floor, or wearable pieces. One of your recent works, An Outfit for Everyday Wear, plays with the idea of monuments. Can you expand on exploring this idea and how it initially came to you?

That work was part of an exhibition called Monument curated by Dionne Hooyberg for the Bunbury Regional Art Gallery. It was an exhibition that invited artists to consider their own understanding of what a monument is and what it could be.

Much of my earlier work was made as things that could be worn outside of a gallery context and this kind of thinking around textile work in public space informed An Outfit for Everyday Wear. I kept coming back to the idea that monuments are almost always about power or death; old men on horses, military figures, grand abstract forms that tell us what’s meant to be remembered. They lock certain values in place and quietly suggest who or what matters enough to be monumentalised.

An Outfit for Everyday Wear started as a way of questioning that logic. Rather than monumentalising power or conquest, I wanted to think about what it might mean to monumentalise the living; specifically, the worker, the exhausted, the ordinary person carrying the weight of daily life. At the moment, that effort can feel endless, even Sisyphean, and yet it’s rarely marked or acknowledged.

Emma Buswell, An Outfit for Everyday Wear, 2025. Courtesy the artist and AVA.

I wanted to create a sort of uniform to articulate that effort, and for this work, it takes the form of a knitted tracksuit, laid flat and lying in state. It draws from the language of statues, plinths, and memorials, but translates those forms into something soft, domestic, and wearable. A garment associated with comfort and leisure becomes an artefact of quiet resistance.

I’m particularly interested in how labour, especially women’s handcraft, is rarely understood as monumental, despite its endurance and repetition. Knitting in this work and in my wider practice becomes both a form of care and a political gesture, a way to think through exhaustion, productivity, and worth. The work asks what might happen if we honoured the everyday instead of the exceptional, and whether small acts of making could stand as monuments to persistence within late-stage capitalism.

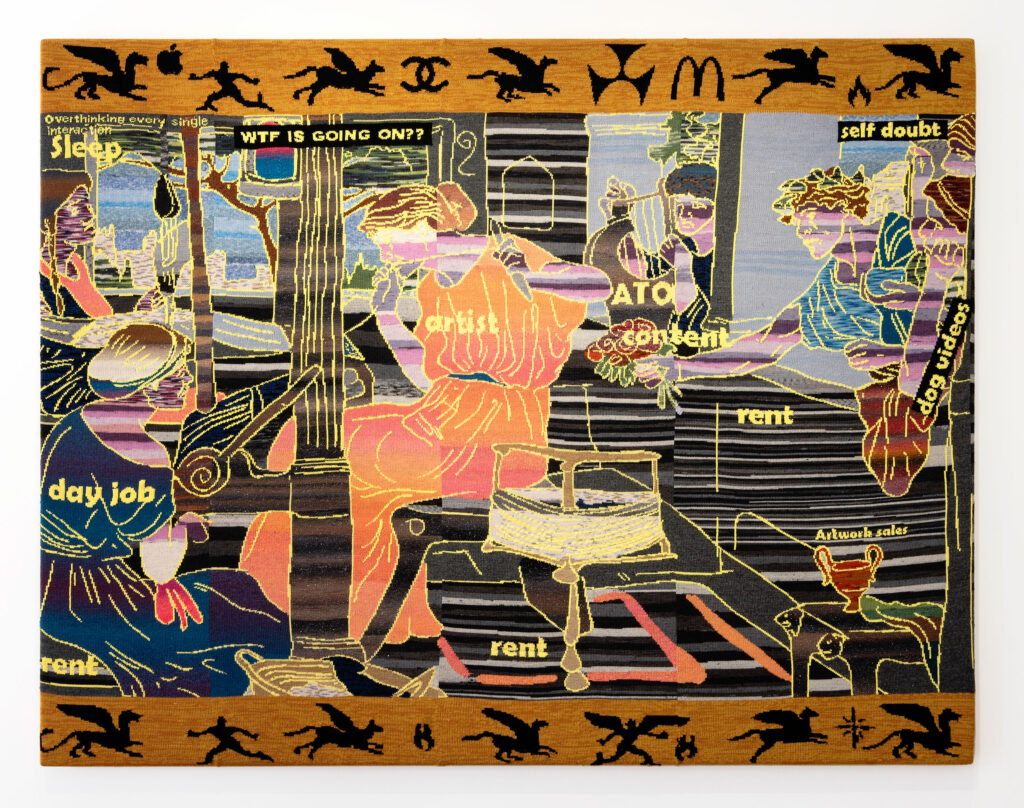

What will you be showing at Melbourne Art Fair?*

*I secretly hope it includes a scathing critique on the commercial nature and general havoc of art fairs, but I digress, probably shouldn’t write that as someone who works directly for the fair. BRB while I run and scream into my pillow about how to sell more tickets.

Hahahaha. I’ve been thinking about this work as a disgusting cocktail or unwanted canape that blends 1990’s Microsoft Encarta (thinking the included PC game), a dreaded relative’s tour of Europe through photos on their iPad and the notes section of my phone where all my most mundane and maniacal thoughts are archived. The work takes the form of a knitted tapestry that composites together several images drawn from historical sources, the imagination and art history. At the moment I’ve been thinking about ideas around the spectacle, and also about how the working life of our current society was imagined or envisaged by previous societies and how we may have fallen short of many of those early pseudo utopian ideals. While we may not yet have our flying cars, our jobs are getting taken by the robots. What might it mean to create art, to witness it, in an age where images can be prompted into being. It’s all another big soup really.

Melbourne Art Fair returns 19 – 22 February 2026.

Click here to secure tickets.